How To Create Django Views

Introduction

If you’ve followed along with our Django Development series, you’ve successfully created a Django application that allows users with admin privileges to add comments and posts, via Django’s admin UI dashboard. You’ve also set up data persistence by leveraging MySQL and Django’s object-relational mapping solution models.

In this tutorial, we will create Django views that enable our web application to properly handle web requests and return the required web responses. As defined in the Django docs, a web response can be the HTML content of a Web page, a redirect, or an HTTP error (e.g. 404). The code for the view functions can technically live anywhere in your project, as long as it’s on your Python path. However, there are some popular conventions for naming and placing the file in which these view functions exist, and we will be following these practices.

Once you are finished going through the steps of this tutorial, your Django blog site will pull a recent post into the your-IP-or-domain/post URL.

Prerequisites

This tutorial is part of the Django Development series. In order to complete the exact technical setup in this tutorial, you should have done the following:

- Installed Django and set up a development environment

- Created a Django app and connected it to a MySQL database

- Created Django models

- Connected your application to a Django Admin interface

However, if you have an existing Django setup, you can follow along to better understand how to implement Django views.

Step 1 — Create View Functions

Within your Ubuntu server terminal, you first need to move into the relevant directory and activate your Python virtual environment:

- cd ~/my_blog_app

- . env/bin/activate

Now that your virtual environment is activated, let’s navigate to the blogsite directory where we will open up a Python file and create our first view function.

- cd ~/my_blog_app/blog/blogsite

Open the views file for editing, using nano or the text editor of your choice.

- nano views.py

Upon opening the file, you should see code that looks like this:

from django.shortcuts import render

# Create your views here.

We will keep the import statement that imports the render() function from the django.shortcuts library. The render() function allows us to combine both a template and a context so that we can return the appropriate HttpResponse object. Keep this in mind because with every view we write, we are responsible for instantiating, populating, and returning an HttpResponse.

Next we’ll add our first view that will welcome users to the index page. We’ll import the HttpResponse() function from the Django http library. Using that function, we’ll pass in text to be displayed when the webpage is requested.

from django.shortcuts import render

from django.http import HttpResponse

def index(request):

return HttpResponse('Hello, welcome to the index page.')

Following that, we’ll add one more function that will display the individual post we’re going to create later in the tutorial.

...

def individual_post(request):

return HttpResponse('Hi, this is where an individual post will be.')

Our final views.py file will look like this.

from django.http import HttpResponse

from django.shortcuts import render

def index(request):

return HttpResponse('Hello, welcome to the index page.')

def individual_post(request):

return HttpResponse('Hi, this is where an individual post will be.')

When you are finished editing the file, be sure to save and exit.

Right now, there is no designated URL that these functions are pointing to, so we’ll have to add that to our urlpatterns block within our URL configuration file. With the views added, let’s move on to mapping URLs to them via this configuration file so that we can view the pages we’ve created.

Step 2 — Map URLs to Views

Django makes it relatively convenient for people to design their own URLs to use with their app. This is done in pure Python by using a file commonly referred to as your URLconf or “URL configuration” file.

In order for the web page to be shown, Django first has to determine the root URLconf module to use, then proceeds to look for urlpatterns, a list data structure containing all of the URL patterns. Django then goes through each URL pattern until it finds the first one that matches. Once a match is found, Django finds the associated view, and that view function will receive data pertaining to the URL pattern and an HttpRequest object. If there is a failure at any point throughout this process, an error-handling view is shown instead.

While in the ~/my_blog_app/blog/blogsite directory, open the urls.py file — also known as your URLconf file — for editing. We’ll use nano here to edit the file.

- nano urls.py

Change the file so that it looks exactly like this, with the urlpatterns list as shown below.

from django.urls import path

from . import views

urlpatterns = [

path('', views.index, name='index'),

path('post/', views.individual_post, name='individual_post')

]

When you are finished adding the above lines, save and close the file.

Once we’ve updated the blogsite directory’s URLconf file, we now must include it in the blog directory’s URLconf or else it won’t get recognized. We need to do this because it is set as the ROOT_URLCONF in our settings file. This means that Django is looking at the blog directory’s URLconf for urlpatterns.

To include our blogsite URLconf within our blog URLconf, we’ll need to navigate to that directory.

- cd ~/my_blog_app/blog/blog

Once you are there, you can open the URLconf file with nano or another text editor of your choice.

- nano urls.py

Within this file, we’ll add the following lines to include the /blogsite/urls.py file we have just worked with, which is indicated in the second line.

from django.contrib import admin

from django.urls import include, path

urlpatterns = [

path('admin/', admin.site.urls),

path('', include('blogsite.urls'))

]

Save and close the file.

Now let’s open a web browser in order to navigate to the URLs we’ve created and verify that they show the text we’ve added to the views. We’ll need to move into the parent directory to access the manage.py file that serves the Django app.

- cd ..

Issue the following command, replacing your IP address below.

- python manage.py runserver your-server-ip:8000

Within your web browser, navigate to the following URL:

your-server-ip:8000

You will see a webpage that looks like the following:

Next, navigate to the following URL:

your-server-ip:8000/post/

From here, you should see the following displayed:

We have now verified that the two urls.py files work, and the data shows us exactly what we’d expect. With this working, let’s add some real data into our blog.

Step 3 — Create a Blogpost

Now that you understand the basics of URL patterns and views, let’s add a blog post and get that to show on the webpage instead of the text we’ve hardcoded into the Python files.

We’ll create a post through the admin page we’ve created. With your server serving the Django app, use a web browser to navigate to the admin Blogsite page at:

your-server-ip:8000/admin/blogsite/

In the interface, click the + Add link located in the Posts row to start populating the database with an example blog post.

Upon clicking the link, you will see an input form that looks like this:

Whenever you want to add a post, you’d go to this page to do so. Alternately, you can edit posts with the Change link.

In the form, you’ll see the following fields:

| Field | Content |

|---|---|

Title |

Add your desired blog post title here, for example My First Blog Post. |

Slug |

This refers to the part of a URL which identifies a valid web address element with human-readable keywords. This is generally derived from the title of the page, so in this case we can use my-first-blog-post. |

Content |

This is the body of your blog post. We will just be adding Hello, World! for example purposes, but this is where you can be verbose. |

Author |

In this field, add your relevant name or username. We will use Sammy. |

Fill out the blog post form as you see fit for your testing purposes.

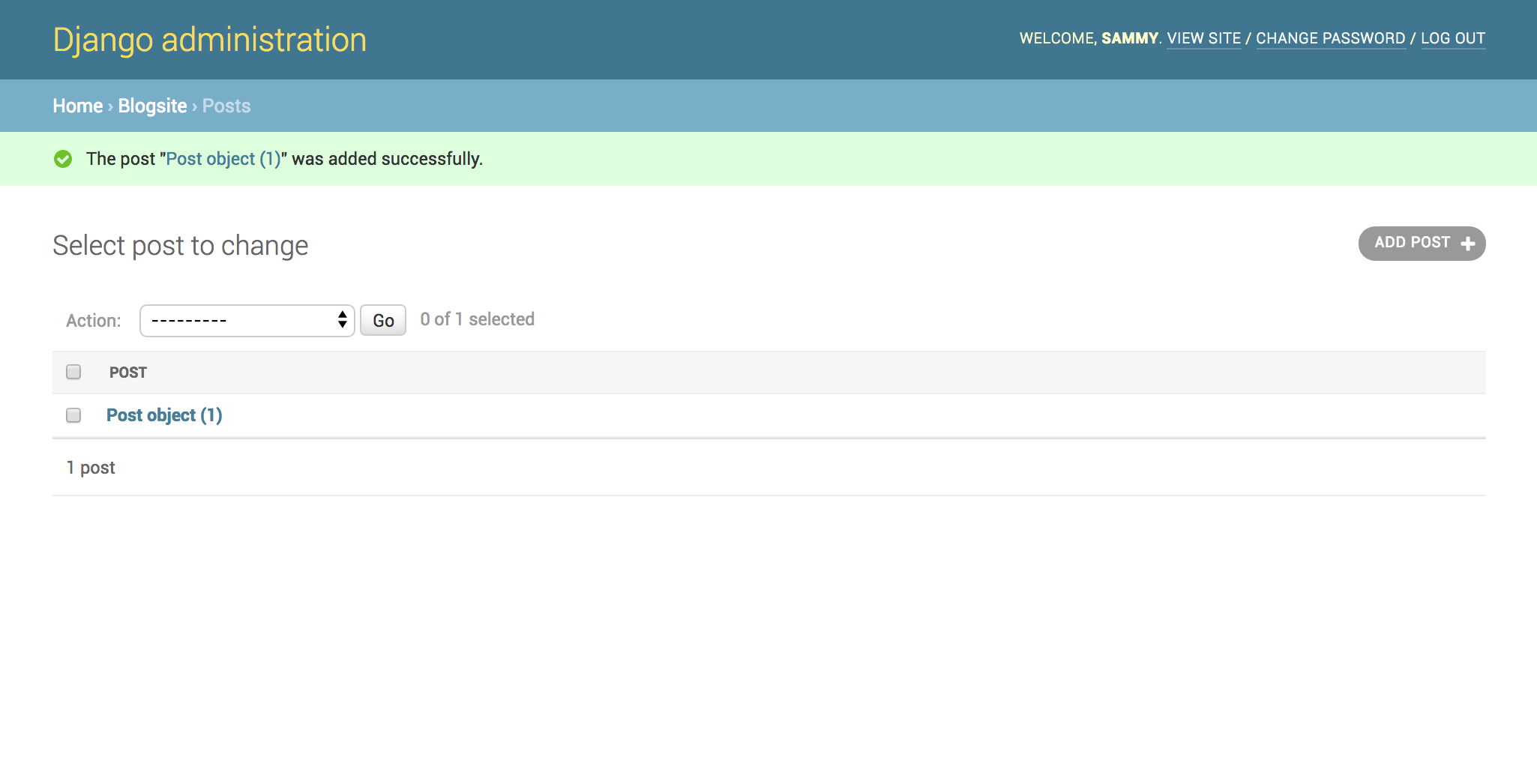

Once you have added example data into the page, click the SAVE button. You’ll receive the following confirmation page:

Congratulations! You’ve created your first blog post!

Next, let’s verify that it has added a row containing the data we’ve added to the MySQL database.

Step 4 — Display Database Data

At this point, we need to move into MySQL, so stop the current server process via the terminal by typing CTRL + C, then open up your MySQL interpreter:

- mysql -u root

Once you’re in the MySQL prompt, move into the blog_data database:

- use blog_data;

Then display the contents of the blogsite_post table.

- select * from blogsite_post;

You’ll receive output similar to the following, which should display the information you added into the admin user interface.

Output+----+--------------------+--------------------+---------------+----------------------------+--------+

| id | title | slug | content | created_on | author |

+----+--------------------+--------------------+---------------+----------------------------+--------+

| 1 | My First Blog Post | my-first-blog-post | Hello, World! | 2018-04-24 17:10:00.139735 | Sammy |

+----+--------------------+--------------------+---------------+----------------------------+--------+

1 row in set (0.00 sec)

As shown in the output, there’s a row with the data for the post we’ve added. Now let’s reference this data into the view function for posts. Use CTRL + D to exit the MySQL interpreter.

Navigate to the location of the views.py file inside of your blogsite app.

- cd ~/my_blog_app/blog/blogsite

Now open the file, so that we can include our new data.

- nano views.py

Edit the file to make it look exactly as shown below.

from django.shortcuts import render

from django.http import HttpResponse

from .models import Post

def index(request):

return HttpResponse('Hello, welcome to the index page.')

def individual_post(request):

recent_post = Post.objects.get(id__exact=1)

return HttpResponse(recent_post.title + ': ' + recent_post.content)

In the code above, we added an additional import statement for Post. We also removed the quoted string from the HttpResponse and replaced it with the data from our blog post. To reference data for a particular object, we’re using the blog post ID associated with the object we’d like to show, and we’re storing that ID in a variable called recent_post. We can then get particular fields of that object by appending the field with a period separator.

Once you have saved and closed the file, navigate to the location of the manage.py file to run the Django app.

- cd ~/my_blog_app/blog

- python manage.py runserver your-server-ip:8000/post/

From a web browser, navigate to the following address:

your-server-ip:8000/post/

Here, we’ll see the changes we have made; the page will look similar to this, displaying the text you added to the post.

When you’re finished inspecting the page, press CTRL + C in the terminal to stop the process from running.

To deactivate your programming environment, you can type the deactivate command and then exit the server.

Conclusion

In this tutorial we have created views, mapped URL patterns, and displayed text on a web page from our blog post database.

The next tutorial will cover how to actually make this more aesthetically pleasing by using HTML to create Django templates. So far, this series has covered Django models and Django views. Templates are the last crucial part when it comes to the foundation of your Django application.

4 Comments